Posthumanism deconstructs the human without knowing what to do with what’s left.

My journey down the rabbit hole of posthumanism

The word ‘posthuman’ implies that some version of us (humans) exists beyond the current one. Not to be confused with ‘transhumanism’ - a philosophical and cultural movement that advocates for using advanced technology to enhance human physical and cognitive abilities (Bostrom, 2016), there is a subtle distinction between the wording that signals very different flight paths for humanity.

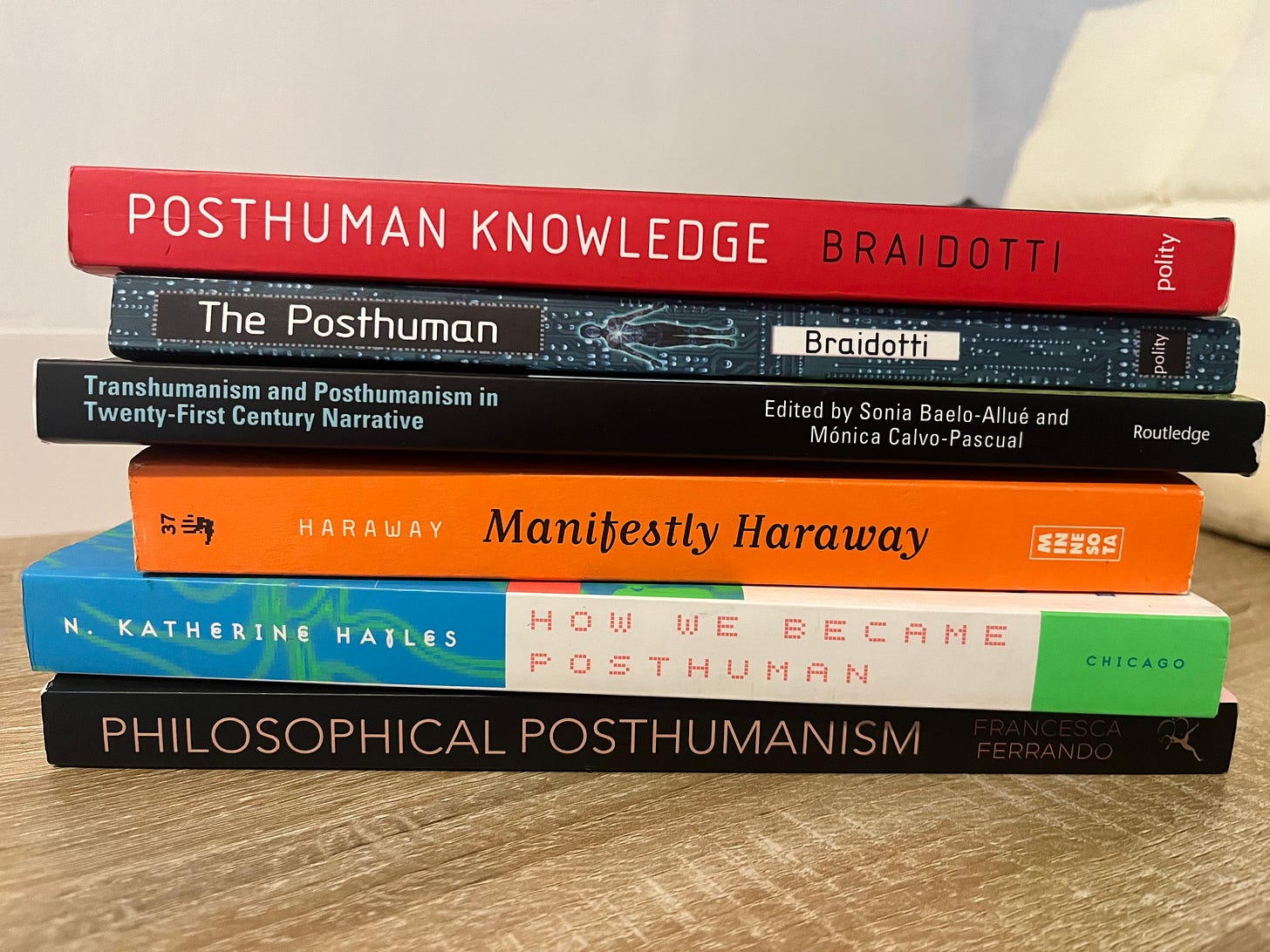

Some light reading

You might think it curious that I picked this topic to break a two-month silence on the blog. The truth is, the ‘posthuman’ movement has been bothering me for a while, ever since a theme surfaced in my doctoral research. Starting in 2002, I began to interview students aged 11-15 years about Artificial Intelligence (AI). I was interested in exploring student voice in relation to this disruptive technology when something strange happened. The children kept referring to AI as ‘they’. Spooky. But what did they mean?

What is posthumanism?

Rosie Braidotti, a pioneer in the field defines it as “a critical framework that questions human exceptionalism by decentering the human in modern thought and examining the interconnectedness of human, non-human, and technological elements.”

If we unpick this, some interesting themes and implications are lurking beneath the words.

As a critical framework, Posthumanism challenges the traditional notion of the human as exceptional. It argues that humans are not the sole measure of value, knowledge, or consciousness, and that other forces are at play. These forces are ‘non-human’ and might appear in the form of technology, AI, biology, and ecology.

As a field of research, it takes its roots from established ways of thinking about the world. Humanism is the obvious starting point - a position that places Humans as the dominant and moral centres of the universe (Descartes, Kant). There are also traces of Postmodernism, specifically in relation to metaphor, narratives and how we see ourselves in these technologies (see Technologies of the Self by Foucault). AI and cybernetics offer the promise of human enhancement, merging biology and synthetic entities to form an entanglement of sorts. Above all, the work of Donna Harraway and Rosie Braidotti, driven by feminism, dominates the posthuman landscape - hinging around hierarchies, gender, race and identity. But, despite these strong foundations, I have found it to be a messy, fragmented, and often self-contradictory field. It has intrigued me and frustrated me in equal measure. It refuses to be one thing. Instead, it is an entanglement of many things, living and otherwise, and this confuses me. I am not alone.

My struggles with posthumanism

Before I spiral into what I don’t like about it, there are some positives.

In an age where humans have altered the planet’s climate and ecosystems, posthumanism calls for rethinking ethics, beyond the human, toward planetary responsibility. It rejects the idea of a detached ‘mind’, insistng that knowledge, thought, and identity are always embodied, material, and interconnected with environments and technologies. I like this, and such a mindset shift would do wonders for how we treat the planet and ourselves. However, there is a darker side to it. In no particular order, here are my issues with it:

Competing epistemologies

Conceptually, I feel there is a vagueness to posthumanism. It is really hard to categorise as there are so many versions of it. There is critical posthumanism, philosophical posthumanism, transhumanism, and new materialism, and they don’t all agree. Some place the human as the centre of everything, others seek to ‘dehumanise’ us. These elastic definitions make it messy and hard to categorise.

Speculative Futures

Our obsession with defining what comes next encourages fields like posthumanism to exist. Perhaps we need it to separate ourselves from other living entities and accept once and for all that we can’t predict the future. Speculating what might happen is a profitable business, so this is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Colonial Bias

Like most emergent technological movements, posthumanism suffers from inherent bias. In this sense, posthumanism is intellectually bold, but dangerously fragile. History favours the winners, and post-human ways of thinking carry Eurocentric assumptions. Many non-Western philosophies (Ubuntu, Confucianism, Indigenous worldviews) already valued interconnectedness long before posthumanists claimed it as their own territory.

Full of contradictions

This is a field that claims to reject human exceptionalism but still uses human frameworks (ethics, logic, reason) to argue its points. It leans on human language and borrows words from biology and the natural sciences to suggest our future will be an entanglement with non-living matter, a symbiosis of sorts. In this sense, it’s a movement that can’t escape what it tries to transcend.

Tech Bias

Posthumanism is overly theoretical to the point it starts to drift into sci-fi at times. It is also a challenging read. Much of the writing (especially in the humanities) is steeped in dense language from Deleuze, Haraway, and Braidotti, high on abstraction, and speculative fictions low on practicality. Assuming everyone has equal access to a technological future also ignores the fact that many don’t, and won’t. This is a contentious point. In celebrating ‘hybridity’ and ‘fluid identities, ’ it often ignores real-world structural issues like poverty, racism, and global inequality. And the fact that the planet is heating up.

In summary

While posthumanism offers valuable perspectives on rethinking our relationship with the planet and technology, it remains frustratingly fragmented and disconnected from practical concerns facing most of humanity. I gave it a good go. I estimate some 50 hours I will never reclaim. It taught me one thing, in trying to go beyond the human, posthumanism ends up face-to-face with the strange reflection of what it just erased.

Alex